Mycelium is a natural material taking over the sustainable design world one industry at a time! A Netherlands-based company is hopping on that train – they are experimenting with mycelium and computational design to create a series of 3D-printed urban reefs that will stimulate water circularity and biodiversity. In simpler terms, your concrete jungle where dreams are made of will be more jungle and less concrete so more living organisms can thrive!

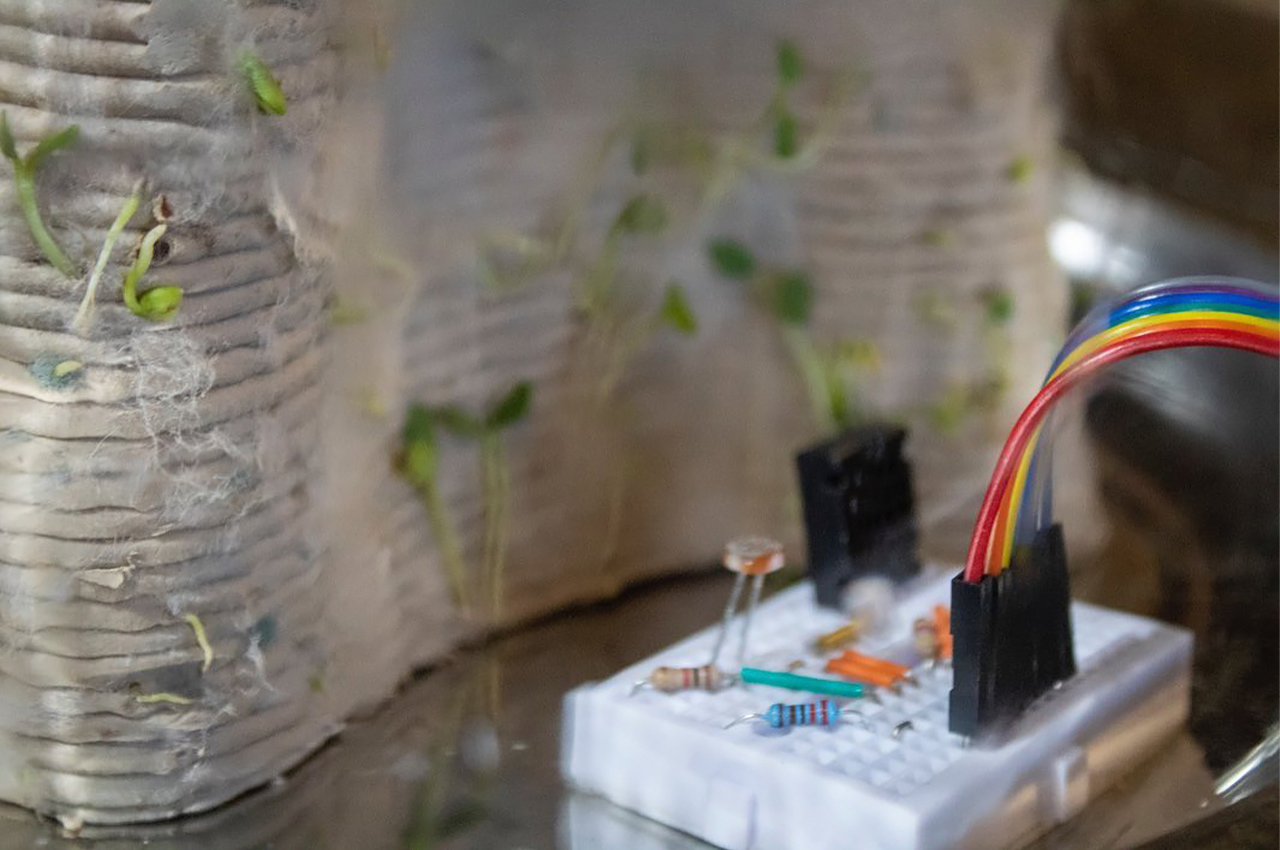

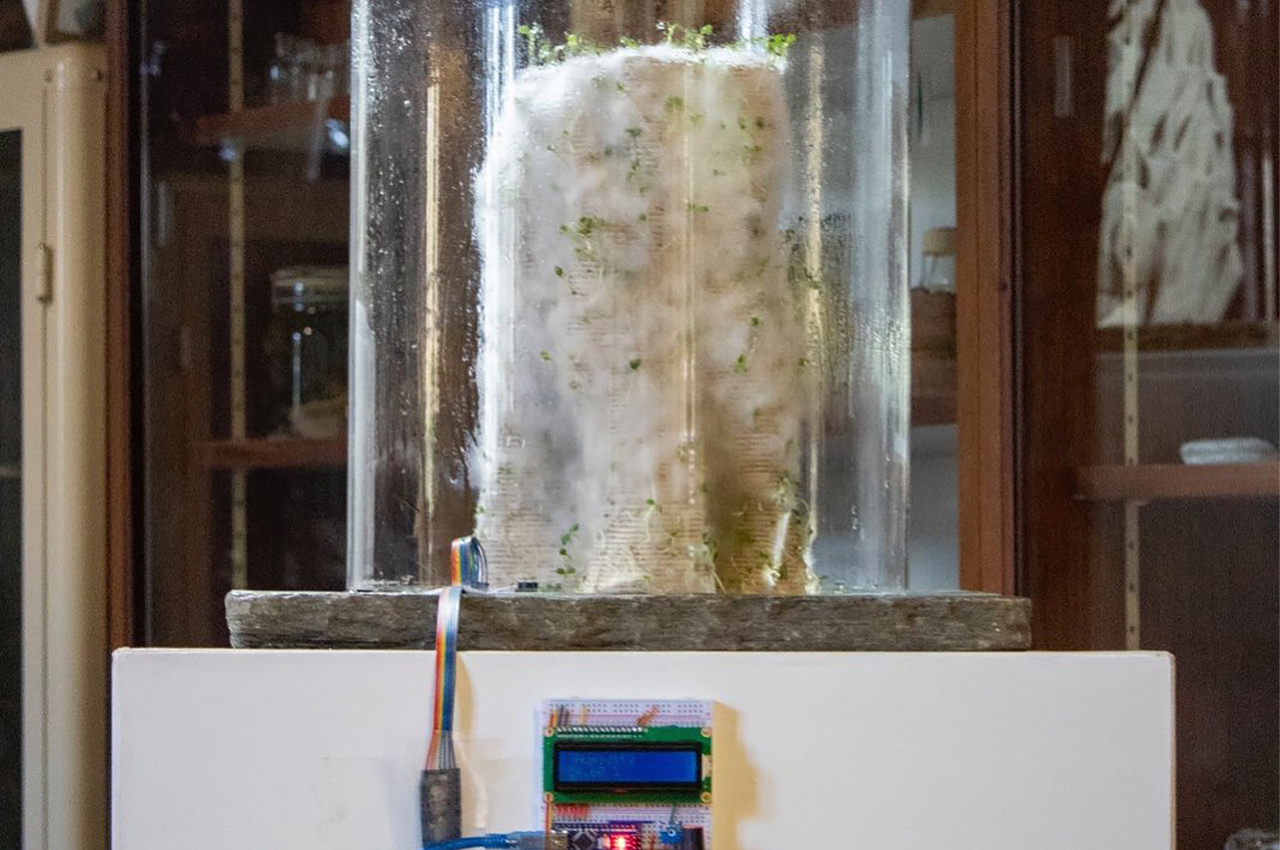

Dutch designer duo Pierre Oskam and Max Latour came up with this innovative solution to make cities more biodiverse. It involves using natural materials to create structural ecosystems that can be integrated within existing environmental elements (eg. fountains). A 3D printer is used to create complex geometrical designs with porous materials like ceramics and composites (made from coffee grounds and mycelium). The moisture in the air is able to pass through and create the perfect environment for various fungi to grow thus bringing the structures to life!

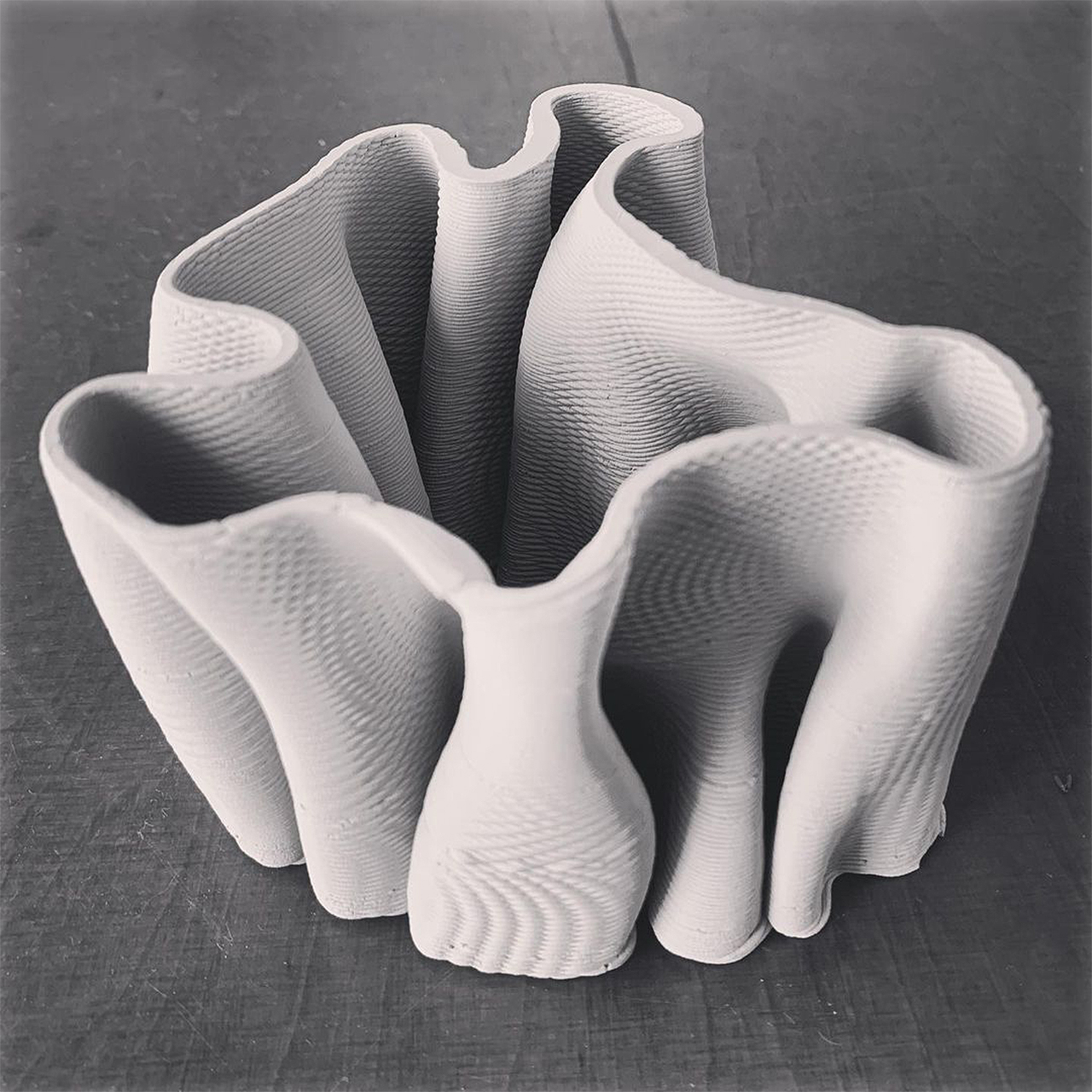

“The most feasible option we are working with is ceramics, but since baking it requires a lot of energy we are investigating more sustainable alternatives,” says Latour and that’s why they are experimenting with materials made from coffee and algae. The team has developed two concept products as a result of their research – the first one is called “Rain Reef” rain collector with an undulating shape that increases the contact area of the water and the potential hatching surface for vegetation and the second is called “Zoo Reef” which is an alternative to fountains in cities.

Rain Reef is 3D printed with a porous material (made from a mixture of seeds, coffee grounds and mycelium), which gets saturated with the collected rainwater, making it accessible to vegetation growing on the outside. The intention is to develop a printable material that is porous, durable, sustainable and bio-receptive. Rain Reef can help collect water in cities where concrete is predominant and rainfall goes in the drain.

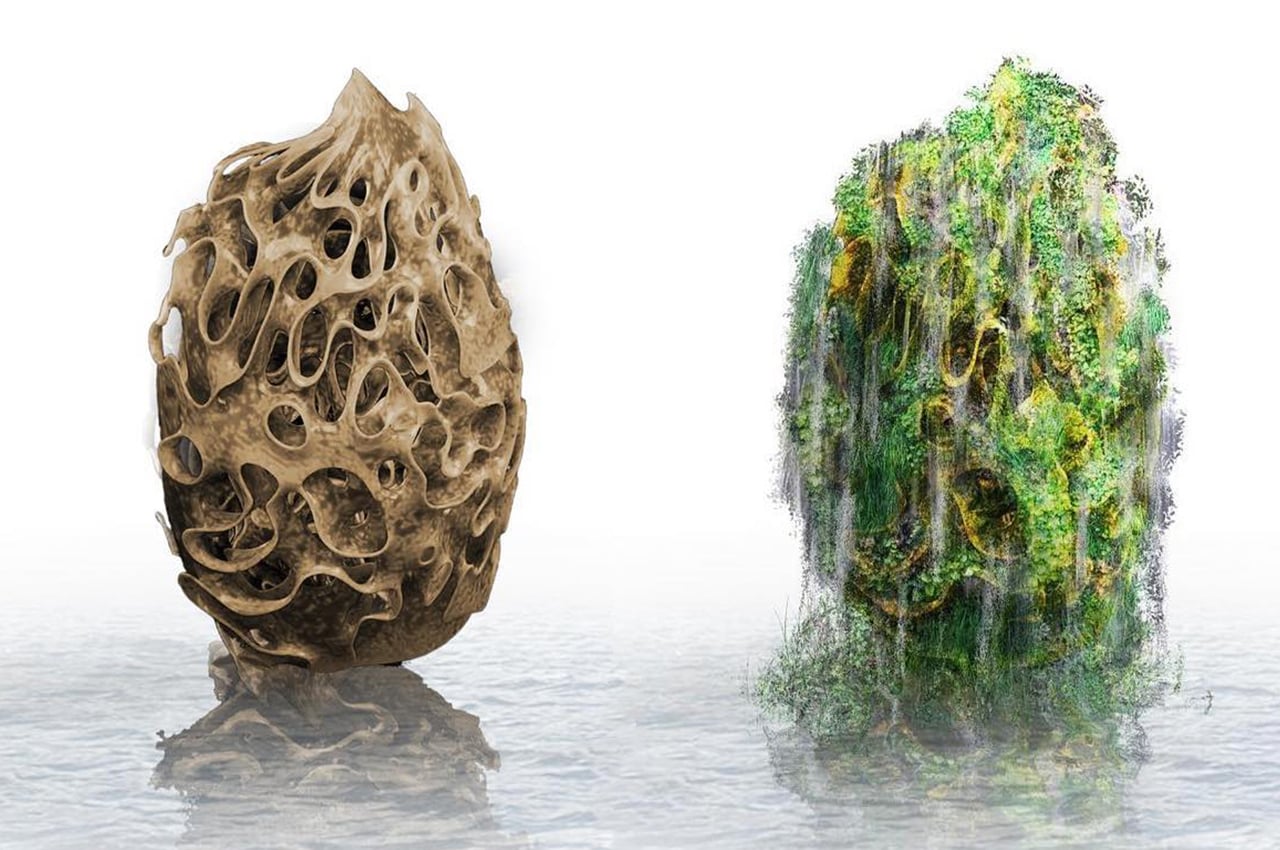

Meanwhile, Zoo Reef is intended to be a substitute for fountains in cities. “There is a lot of potential for biodiversity stimulation around urban fountains. We propose a complex labyrinth of spaces that are all interconnected. By differentiation in sizes, orientation regarding sun, wind and rain, varieties of microclimates would develop,” says Oskam.

“At Urban Reef we consider the city as a potential habitat to organisms, not exclusively humans,” the duo explains. “We position ourselves as human within the natural environment deviating from the modernist view of the human transcending nature. From that perspective, we aim to gain a profound knowledge of natural processes to both integrate those in our design methods as well as design with ecologies in mind.”

Rather than determining top-down where the organisms should live, these Urban Reefs create a new range of potential habitats. Even though they are still in the early stages of research and development, Latour and Oskam’s project has the potential to be scaled and make an impact through real-world applications in the near future because the technology and materials exist. It’s similar to a living wall, except in this case the choice of materials and the structural design promotes their integration within cities without human intervention.

Designer: Pierre Oskam and Max Latour